TOP FIVE PIECES OF CLASSICAL GOTH

By Patrick Neas, KC Arts Beat

Before there was The Cure or Dead Can Dance, the spirit of Goth was captured in all its morbid glory in various works of classical music. With themes of death, despair and existential dread, Classical Goth sounds especially good this time of year, when darkness descends and the smell of damp decay fills the air. So here are my Top Five Pieces of Classical Goth because sometimes it’s good to explore the dark side in order to appreciate the light.

As an Amazon associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

No. 1: Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 4

If you want music that expresses the futility and pain of existence, this is the symphony for you. Heavily influenced by Mahler, it has Mahler’s depressed gloom with the added touch of Shostakovich’s suffering under Soviet totalitarianism. One understands why this symphony, which was written between 1935 and 1936, was shelved for 30 years and Shostakovich was put on Stalin’s shit list. No joyful optimism in a bright socialist future here.

The symphony belches fire and smoke like an infernal machine. Certain sections have a crunching, grinding industrial sound reminiscent of German noise band Einstürzende Neubaten. The final movement, which concludes with the celeste fading off into nothingness, is the musical equivalent of entropy finally overcoming the universe until the last star goes poof. That’s a scenario any nihilistic Goth could appreciate.

Gennady Rozhdestvensky’s recording with the U.S.S.R. Ministry of Culture Orchestra is a classic that captures every last drop of turmoil. You can often snag an affordable used copy on Amazon. If not, a great runner up is Andre Previn’s reference 1977 recording with the Chicago Symphony. Previn unleashes all the psychological tension and violence coiled up in this intense masterpiece.

NO. 2: ALBAN BERG’S WOZZECK

With its themes of madness, despair, alienation, and grotesque violence, Wozzeck is the ultimate Goth opera.

It tells the story of Wozzeck, a poor soldier, who is subjected to humiliation, medical experiments and emotional betrayal. His descent into madness is portrayed with harrowing intensity, culminating in murder and suicide. The opera ends not with redemption but with a child discovering his mother’s corpse, underscoring the bleak, cyclical nature of suffering.

Berg’s atonal score, dissonant textures and fragmented forms mirror Wozzeck’s fractured psyche. The music itself becomes a gothic architecture of torment. One of the best-ever recordings of Wozzeck is with the Vienna Philharmonic conducted by Claudio Abbado. Recorded in 1987, it features Franz Grundheber as Wozzeck. His portrayal is raw, haunted, and deeply human—widely praised as definitive. It’s on the Forbes list as one of the “13 Best Recordings of Claudio Abbado.”

NO. 3: ARNOLD SCHOENBERG’S PIERROT LUNAIRE

Leonard Bernstein said, “This is a piece which never fails to move and impress me, but always leaves me feeling a little bit sick. This is only just, since sickness is what it’s about — moon sickness.” In this series of songs, Pierrot, the lovelorn clown of Commedia dell’arte, descends into lunacy, haunted by visions of blood, death, and distorted reality. The cycle’s fragmented structure and atonal language mirror his unraveling psyche. Schoenberg wrote Pierrot in 1912 when German expressionism was making its mark in the paintings of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Oskar Kokoschka and Emil Nolde, and was soon to exert a strong influence on films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Nosferatu. Like those works, Pierrot Lunaire explores madness, moonlit obsession, grotesque imagery, and existential fragmentation. It’s one of the great musical masterpieces of the 20th century.

Pierre Boulez was one of the greatest champions of Schoenberg’s music and his recording of Pierrot Lunaire with Ensemble Intercontemporain and soprano Yvonne Minton is nonpareil. Minton has a natural feel for Schoenberg’s half singing/half speaking sprechstimme, snarling and spitting like a diva in a dark and dingy Goth nightclub.

No. 4: KRZYSZTOF PENDERECKI’S DIES IRAE

There is something innately goth about the Latin hymn Dies Irae (“Day of Wrath”). Describing the Last Judgment, fire, and divine terror, this chant has long been a gothic musical totem, used by composers from Berlioz to Ligeti to evoke doom. But no composer has given it more horror than the Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki. His Dies Irae (1967) is a 20-minute cantata for soprano, mezzo-soprano, bass, three mixed choirs, and orchestra. It was composed to commemorate the victims of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp and was premiered at the site itself.

The music is brutal and expressionistic—clusters of shrieking strings, choral wails, and percussive violence. It uses sirens, chains, whips, scrapers, and other unconventional sound effects to evoke horror, chaos and ritualistic violence. This is music that will haunt your dreams.

Polish conductor Antoni Wit has recorded all of Penderecki’s music for the Naxos label. He has this music in his bones, and in the Dies Irae, he perfectly expresses Penderecki’s vision of the Nazi horror. This is very difficult music to listen to, but it’s music that continues to have powerful relevance.

No. 5: RICHARD STRAUSS’S SALOMÉ

Gustave Moreau’s The Apparition

There is one opera that might rival Wozzeck as the most goth opera ever written, and that is Richard Strauss’s Salomé. Strauss closely followed Oscar Wilde’s scandalous play about the beheading of John the Baptist and created an equally scandalous opera. He fused erotic obsession, religious blasphemy, and grotesque violence into a psychologically intense, expressionist work that revels in death, desire and decay.

You may have seen one of Gustave Moreau’s many paintings depicting Salome with the disembodied head of John the Baptist. Strauss’s opera is a Moreau painting come to life. Salome’s lust for John the Baptist culminates in necrophilic ecstasy—she kisses his severed head in the opera’s climax. You can’t get more gothic than this fusion of desire and death.

Strauss’s score is lush, dissonant, and feverish. It uses chromaticism, leitmotifs, and orchestral extremes to evoke hysteria, obsession, and doom. One of the most infamous scenes is the Dance of the Seven Veils, which is both striptease and ritual sacrifice. Salome sheds layers of identity, revealing her raw, destructive desire.

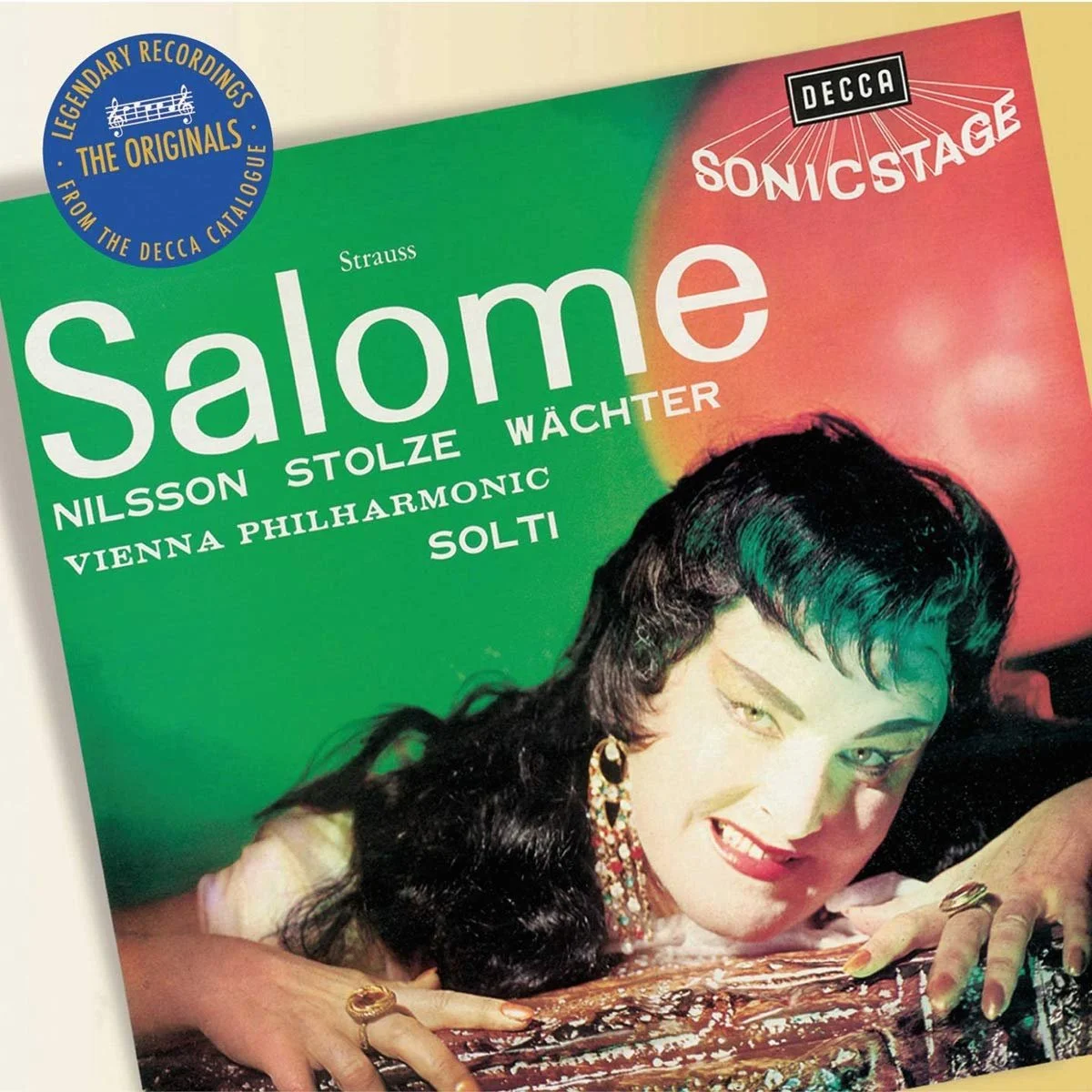

Strauss’s score is lush, dissonant, and feverish. It uses chromaticism, leitmotifs, and orchestral extremes to evoke hysteria, obsession, and doom. Sir Georg Solti had a real feel for this kind of over-the-top German late Romanticism, and he pulled out all the stops in his 1962 recording with Birgit Nilsson in the title role. Nilsson’s voice had gleaming clarity, formidable stamina, and laser-like projection—perfect for Strauss’s dense orchestration and soaring climaxes. She portrayed Salome not as a fragile girl but as a terrifying force of obsession and defiance.

For 25 years, Patrick Neas was program director and host of the morning show on Kansas City’s classical radio station, KXTR and was also the long-time classical music writer for the Kansas City Star. He has an extensive classical CD collection, and he loves sharing his knowledge of recordings and making recommendations.