RESTORATION RADIANCE

Musica Vocale Presents Hail Bright Cecilia: A Purcellian Feast

By Patrick Neas, KC Arts Beat

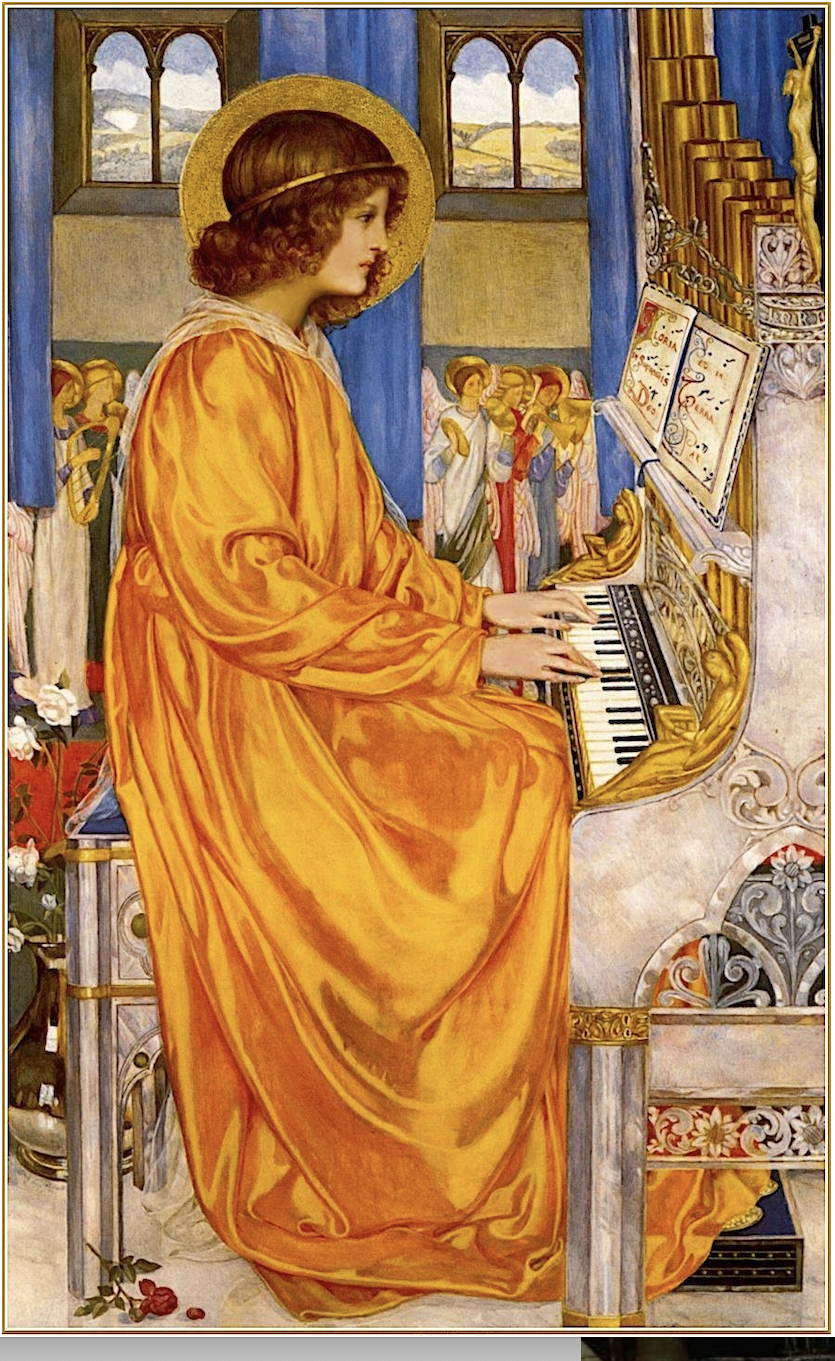

St. Cecilia Window (1902), Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral

Henry Purcell stands as one of the most remarkable figures in English music, a composer whose work seems to hold an entire era inside it. His music carries the elegance of the Restoration court, the gravity of Anglican liturgy, the vitality of the London stage, and the wit of a man who lived fully in his time.

Musica Vocale, with musicians from Kansas City Baroque Consortium, will perform a program entirely devoted to Purcell, Hail Bright Cecilia: A Purcellian Feast, at 3 p.m. March 29 at Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral.

Purcell’s output is astonishing in its breadth. Jay Carter, Musica Vocale’s artistic director, says “there is such a variety of it. There is opera, there are odes that were written for court and for public performances, church music, anthems. There is just so much musical material.”

What makes this variety even more striking is the brevity of Purcell’s life. Born in 1659, he died in 1695 at the age of 36, yet he left behind a body of work that rivals composers who lived far longer. Carter observes that “what we do have is exceptional music and some of the best writing of English text into a musical form that anybody could have ever done.”

To understand how Purcell achieved so much so quickly, one must look at the England he was born into. The year 1659 found the nation emerging from civil war, plague, and the Puritan suppression of the arts. When Charles II returned from exile in 1660, he brought with him a hunger for music, theater, and spectacle. He had spent his exile at the court of Louis XIV, absorbing the refinement of French musical culture. Determined to recreate that brilliance in London, he invested heavily in rebuilding the Chapel Royal and the theaters.

Charles II

Henry Purcell

Purcell entered this world as a child prodigy. He joined the Chapel Royal as a singer at the age of seven, where his teachers had been directly shaped by the king’s French influences. Carter explains that Purcell “learns the French style secondhand” through mentors like Pelham Humphrey and Henry Cook, both of whom had studied at the French court. His earliest surviving work, written at age eleven for the king’s birthday, “sounds like a piece of Charpentier or Lully,” Carter said. Yet even in these youthful works, one hears the seeds of something distinctly English.

This blend of influences is part of what gives Purcell’s music its unique character. Carter agrees that his music sounds unlike that of any other Baroque composer. The French influence appears not in surface imitation but in deeper structural ways. “Part of it has to do with text declamation,” he said. French sung drama prized clarity, expressive repetition, and harmonic boldness. Purcell took these principles and fused them with the lingering English traditions of Tallis, Byrd, and Gibbons. The result was a musical language that could be serene one moment and unsettling the next. Carter recalls hearing Purcell for the first time and feeling “so calm and then all of a sudden I was on edge and I did not know why.” That tension is one of Purcell’s signatures.

Purcell’s life, like his music, was full of contrasts. He was court composer for James II and William and Mary, a church musician, and a man who wrote drinking songs like My Lady’s Coachman John, with lyrics that still raise eyebrows. Carter laughs as he recalls some of these pieces. “He wrote several,” he said. “Some of them are written as rounds, and when the third part comes in, you hear the interplay of text between the voices, and they are absolutely ribald.” This earthy humor reminds us that Purcell was not a cloistered sacred composer but a full participant in the Restoration’s exuberant cultural life.

Henry Purcell

James II

The centerpiece of the program and the work which gives the concert its title is the 1692 ode, Hail, Bright Cecilia, with a text by Nicholas Brady and John Dryden. This is the first time the work will be performed in its entirety in Kansas City.

Saint Cecilia has long been regarded as the patron saint of music, a symbol of the spiritual and emotional power that song can carry. Her feast day became a focal point for English composers beginning in the seventeenth century, inspiring Purcell to write some of his most radiant ceremonial works. Handel later continued the tradition with his own Cecilian ode, and centuries after that Britten revived it with his Hymn to Saint Cecilia, written during the Second World War. Across these eras, Cecilia represents the enduring belief that music can restore, uplift, and bind communities together

St. Cecilia by Ann Bunce (1901)

St. Cecilia by John Melhuish Strudwick (1896)

Surrounding the majestic ode for St. Cecilia are anthems written for royal occasions, including I Was Glad, composed for the coronation of James II, and Rejoice in the Lord Alway, one of Purcell’s most beloved symphony anthems. These pieces reveal Purcell at his most radiant, a quality Carter finds especially meaningful today. “There is something so jubilant and optimistic about his music, and that is something I particularly need in my life right now.”

Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral is an inspired setting for this program, not only for its acoustics but for its visual and symbolic resonance with Purcell’s world. Carter points out that “there is a beautiful stained glass window at Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral on the right hand side of the nave, a St. Cecilia window. Then there is another one right next to it that is a picture of David playing the harp. They are such striking images. It seemed like our program would be such a good fit with the Englishness of the space and all of the other things rolled together.” The cathedral’s architecture with its luminous windows and sacred atmosphere amplify the emotional and historical depth of Purcell’s music. It is a space where the English choral tradition feels not only appropriate but inevitable, a place where the past can speak with clarity and warmth.

Musica Vocale is one of Kansas City’s most distinguished choral groups, with a lineage going back to its founder, the legendary choral conductor and teacher Arnold Epley. Carter describes the ensemble as “a happy ensemble of people who like to get to do the work that we are getting to do.” You can hear that joyin their performances. Their singers include church musicians, educators, highly trained amateurs and professionals who produce a sound far larger than their numbers suggest. What sets Musica Vocale apart is not only its artistic excellence but its commitment to accessibility. Through the generosity of donors and the ensemble’s own thrifty stewardship, they make their concerts free to the public. In a cultural landscape where cost can be a barrier, Musica Vocale offers world class performances as a gift to the community. It is a rare and admirable mission.

Musica Vocale at Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral

Purcell’s world was not all celebration. The Restoration was a time of shifting patronage and economic uncertainty. When the crown reduced its spending on music, Purcell and his colleagues turned to the theater for income. This may have contributed to the circumstances of his early death, which remains the subject of colorful speculation. Carter notes that one theory involves Purcell being locked out of his house in the rain after a late night. Another involves lead poisoning from chocolate. Whatever the cause, his untimely death cut short a career that might have reshaped English music even more profoundly. Carter reflects on the tantalizing possibility that Purcell and Handel might have met. “If Purcell had lived another decade, we are certain he would have interacted with Handel,” he said. “It would have been amazing to have seen what blended musical life would have been like if they had been in the same place at the same time.”

MUSICA VOCALE PRESENTS HAIL BRIGHT CECILA: A PURCELLIAN FEAST

3 P.M. March 29 at Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral, 415 W. 13th ST.

The concert is free. For more information and to support Musica Vocale, musicavocale.org.

David with His Harp window (1901), Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral